Condition Critical

Healthcare crisis inspires a rally for change

Prince George, June 22, 2000:

The pictures are over a decade old, but the feelings they capture still resonate.

A man dressed in bright green hospital scrubs waves pens and petitions as throngs of people make their way from the parking lot to the Multiplex (now CN Centre). A woman presses the form against her friend’s back and signs; others steady their signatures on handbags.

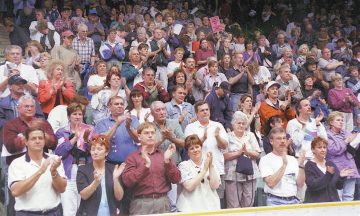

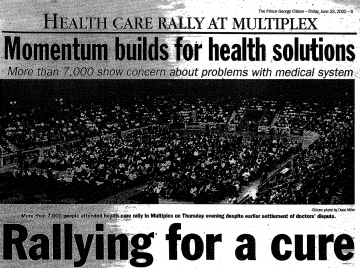

7,000 people from communities across northern B.C. pack the arena from the first aisle to seats just shy of the rafters. They have come to be heard, and many wave hand-painted signs. Their intensity charges the air. There are no Prince George Cougars warming up on the ice, no opening bands wrapped in smoke and lights, no roaring monster trucks or barrel-clad rodeo clowns.

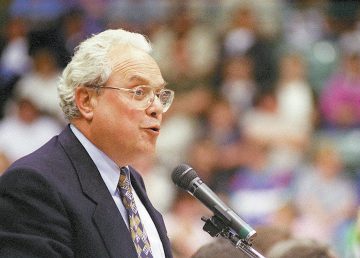

All eyes are on the stage, where University of Northern British Columbia president, Charles Jago, takes the podium and begins his speech.

The sparse, yet essential network of hospitals and clinics throughout the north were facing critical shortages of physicians and health professionals, resulting in emergency room closures, and limited services. Some towns were down to only one family physician, and patients were forced to travel great distances to access essential care. Only five months into the new millennium, the future for many communities looked grim.

But the problems facing northern British Columbia communities weren’t isolated to that region alone. There were numerous vacancies in cities and communities across the province, and many of B.C.’s doctors were aging and would retire within the decade.

Investing in a long-term solution

For years the training and supply of physicians in British Columbia had not kept up with population growth. B.C. produced only 27% of the 300 new physicians needed in the province each year, there were less medical student spaces per capita than any other province, and to make matters worse, B.C.’s budget for medical education was half as much per capita as other provinces.

With such a short supply of homegrown physicians, B.C. was reliant on attracting new graduates from other provinces, or importing foreign doctors from countries where their services were in greater need.

Short-term fixes, like return of service contracts and debt forgiveness for rural practitioners, could help bandage dire situations, but without significant planning and investment in a long-term solution, the health of many marginalized, rural, and remote communities might continue to hover just above flatline.

More doctors were needed, but where would they come from? How could we increase the number of doctors in the places where they were needed — rural and underserved communities far from Vancouver, the centre of medical education, home to large urban tertiary hospitals, and research institutes?